Nationality: Greek

Major Works: The Iliad, The Odyssey

Publication date: 8th century BC

Setting: Mediterranean Sea & beyond

Format: Epic poem, written in hexameters (six “beats” of syllable units per line)

Length (time to read): The Iliad (approx 10hrs 14mins), The Odyssey (8hrs 9mins)

Influences: None, this is the mother lode of Western literature

Themes: War, Fate, Myth, Adventure, Betrayal, “Nostos” (longing for home)

Quotes: “Let me not then die ingloriously and without a struggle, but let me first do some great thing that shall be told among men hereafter” (The Iliad, Book XXII), “It’s the wine that leads me on, the wild wine that sets the wisest man to sing at the top of his lungs, laugh like a fool – it drives the man to dancing … it even tempts him to blurt out stories better never told” (The Odyssey, Book XIV)

Literary Echoes: James Joyce’s Ulysses notably, but see also Dante’s Inferno, Margaret Atwood’s The Penelopiad, Derek Walcott’s Omeros, Tennyson’s Ulysses, etc

Album accompaniment: Disraeli Gears by Cream, notably the track “Tales of Brave Ulysses”

Film accompaniment: O Brother, Where Art Thou? by the Coen brothers

Dave’s synopsis: The Iliad – Paris (from Troy) abducts Helen (from Greece), so Greeks led by Achilles sail to war against Troy led by Hector; long siege comes to a head when sulking Achilles springs into a furious rage after the death of his friend (lover?) Patroclus; Troy burns. The Odyssey – Returning home, one of the Greek military leaders Odysseus is blown off course, and undergoes many trials and challenges, notably from his arch nemesis Poseidon, before making it back to his homeland of Ithaca, where he has to deal with the many suitors to his wife Penelope, who has remained faithful during her husband’s 20-year absence. Another bloody climax.

Rating (out of 100): 99

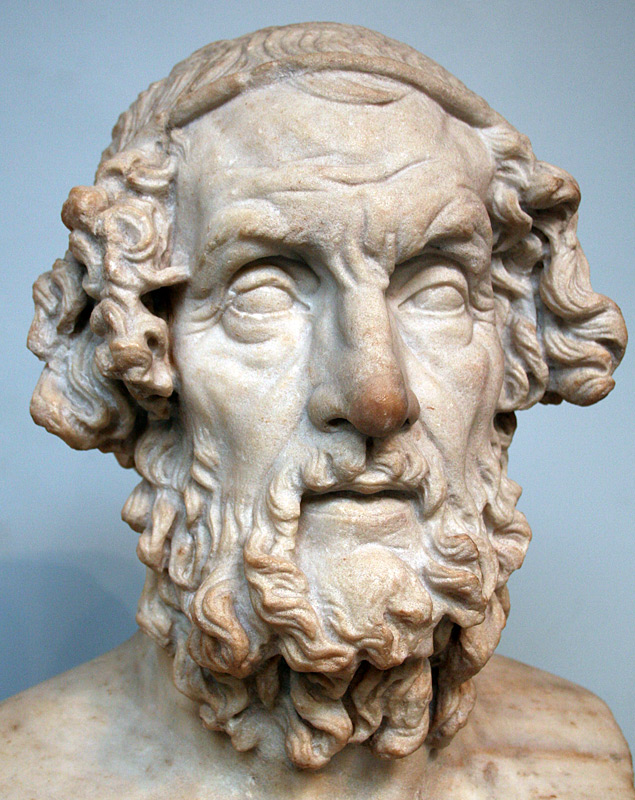

There are two famous Homers in history. This one…

…and the one behind The Iliad and The Odyssey. I nearly put Homer “wrote” them, but truth is they were both epic poems recited orally, often accompanied by the sound of a lyre. Nobody can be sure that both epics were the work of one mind, and the question of authorship hangs over a lot of classic literature (including Shakespeare and even Kafka), but the poems were clearly part of an ancient tradition that produced many classic texts that survive to the present day and form the bedrock of western literature.

Translation

Like all poetry, the works are best appreciated in the original language, but given very few people speak Ancient Greek, most readers have to tackle the thorny issue of choosing the best translation. Inevitably, for such an influential work, there are a wealth of options, and the one that’s long lingered on my bookshelf is the Penguin Classic translation by E. V. Rieu, first published in 1950. While this translation is highly regarded, my preference is always to seek out the best and most modern version, and that’s what led me to Robert Fagles, whose translation is admirable mainly for the clarity of its English (poets are always best at translating other poets). There’s also the added bonus with the Fagles translations that Derek Jacobi narrated the audiobook version of The Iliad and Ian McKellen narrated The Odyssey, helping to bring the epics to vivid life:

Other notable translations are by Richmond Lattimore and Alexander Pope, while Matthew Arnold wrote the supreme essay on translating Homer. The first female translation of The Iliad in English was done recently by Caroline Alexander, and I mean to buy a copy when the paperback version comes out later in 2016, while it’s also worth mentioning the wonderful re-imagining of The Iliad by poet Christopher Logue, called War Music. Also, you can often find publicly accessible versions of the poems by major cultural institutions, such as this one by London’s Almeida theatre (which is available until late 2016).

As for children’s book versions, I think the Marcia Williams books on The Iliad and The Odyssey are best; we also loaned a copy of the Usborne young readers version, which my 6-year old daughter enjoyed a lot (especially when she mastered the pronunciation of Odysseus). This version contains the potent myths, like Achilles’ heel and the Trojan Horse, which are often associated with Homer’s epics but don’t actually feature explicitly in either The Iliad or The Odyssey.

Structure

Both works are divided into 24 books, though it’s not clear if the book structure was imposed later by Alexandrian editors, or whether it was the intention of Homer. Essentially, The Iliad is about war, and how it comes about, and The Odyssey is about picking up the pieces after a war or conflict, and re-establishing peace. In The Odyssey, the homecomings (“nostoi”, root of the word nostalgia) of Odysseus, and more minor characters Nestor, Menelaus and Agamemnon, are detailed at length. The structure of the poems break down as follows (based on this study):

The Iliad has two parts: 1) Wrath & the aftermath, and 2) Reconciliation

The Odyssey has two parts: 1) Return, and 2) Vengeance

In both books, the climax or key turning point (“peripeteia”) occurs in Book 22 out of 24, i.e. Achilles kills Hector in The Iliad and Odysseus kills the suitors in The Odyssey. In the ninth book of both poems, the hero commits an act of hubris that alters their pre-ordained fate, in Achilles’ case it’s refusing Agamemnon’s offer of reconciliation and in Odysseus’ case it’s taunting the cyclops Polyphemus and incurring the curse, enacted by his father Poseidon, that ensures Odysseus returns “late, ill … [and finds] trouble at home”.

“In media res” – both books start in the middle of the action, but The Iliad’s structure is more linear (war with the Trojans has already been going on 9 years and we pick up from there until the end of the war) while The Odyssey’s structure is more complex, with flashbacks to the previous 9 years, and a discernible substructure, Books 1-4 Telemachia, Books 5-12 Odyssey proper and Books 13-24 Nostos (homecoming).

Themes

Achilles’ main qualities are his warrior ethos and concept of “kleos” (fame / glory). I asked Caroline Alexander in a Q&A session on the Guardian website whether The Iliad can teach us anything about modern conflicts, and her response was: “Yes – very much so. For example, at the time of the invasion of Iraq I was reading Book 2, where Zeus mulls over the many ways in which he could turn the tide of battle against the Greeks. And the best option is to send a false dream of victory to their commander and chief. Agamemnon then wakes up raving about how he knows they will take Troy that very day. That’s just one small incident. More powerful is The Iliad’s overarching vision of war, or evocation of war – it’s both true to the warrior ethic, and to the tragic reality of all war’s aftermath.”

The tone is very different in The Odyssey vs The Iliad, the former more bawdy and comic at times, less noble. Odysseus’ three main qualities are his cunning, adaptability and ability to endure, and The Odyssey extends the view of a hero from a noble warrior to a defender of society’s values, shown in the way Odysseus returns to Ithaca and restores order. I also like how sex, drugs and strange beasties (ogres, sea monsters, Sirens) populate The Odyssey – it’s way better than any fantasy novel I’ve ever read. The power of the lotus flower to make Odysseus lose his memory is a potent image, in that it deprives him of the ability to recount his experiences and draw lessons from his journey. The threat of forgetting continues to plague Odysseus, especially with Circe’s drugs and with the Sirens’ song, the main danger being that he may forget to return. Memory counts for an individual, a society and a culture and this is a major theme of the poem.

Fate and character are also key to the action, and massive sulks by gods and men often drive the drama: Achilles not wanting to fight in The Iliad, Poseidon having it in for Odysseus. The gods often intervene too; for example, an identity crisis pervades the second half of The Odyssey, with Odysseus dressing as Nobody and only his dog Argos recognising him – after the big reveal at the end of the book, Odysseus even questions whether his homeland is indeed Ithaca (Athena has to intervene to convince him). At one point, Zeus says that men are as much to blame for their troubles as the Gods.

Betrayal and deception are also key themes. Penelope deceives her suitors with her weaving – saying she won’t remarry until she’s weaved her yarn, then sneakily unravelling it each night – and is as cunning as her husband. Penelope is also faithful, unlike some of the other major female characters in the poems. Helen betraying Menelaus and running off with Paris is the factor that drives the Greco-Trojan War, while the story of Agamemnon’s betrayal by his wife Clytemnestra is often referenced throughout. Adventure is also key to The Odyssey, and is a theme at the heart of many great works of literature; the opening is about a young boy (Telemachus) becoming a man, and it’s as much a journey for him into adulthood as it for Odysseus returning to Ithaca.

Infographics & resources

Odyssey map

Odyssey comic

The catalogue of ships in The Iliad

List of deaths in The Iliad

In Our Time podcast: Odyssey